Prose Poem Sequences

BKMK Press–UMKC, 116 pages, 2003

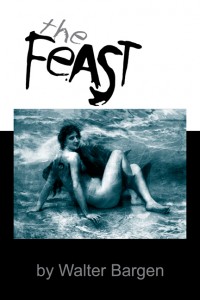

$14.00 (Illustrated by Mike Sleadd)

Selections:

BEING ITS TIME

In a small Baltic town, on a cold overcast day that could have been yesterday a century ago, and for all practical possibilities will probably be tomorrow a century from now, and whose indeterminancy turned the maypole in the hay-stacked field just east of the last half-timbered houses into a spear stuck in the frozen ground by a falling warrior of Valhalla—here Heidegger slipped beyond his and anyone else’s journal. He abandoned future biographers who might scour the town for street corners where the great thinker stood, so they could ponder what he might have pondered, such as seeing his reflection in the window of the shoe-repair shop. He stepped away from the preponderance of philosophers who would keep turning the pages until they were blank as the coming Arctic snow¬. It was there at the small desk in the inadequately heated third-floor room, which was really an attic he rented under an alias, where each breath hinted of the last, that he first wrote that the only thing worth thinking is the unthinkable.

Heidegger had dipped his stork-white quill into the inkwell and flown into the dark, not knowing if he would ever return. There was elation among those who thought he had given birth to the unknown or, less, that he made the improbable probable. Accident became coincidence, coincidence synchronicity, and synchronicity the fine tuning of the cosmos. Whole tired towns swore off potatoes and turnips, and starved, believing they could live on the light of his thinking. These emaciated towns became known as the first voluntary pogroms. A man bloodied his face trying to run through a wall, but the rumor persisted of his success. Throughout the country large bandages flowered over noses, as if an early sign of spring. Women hanged themselves from ceilings, hoping to get closer to heaven, and had to be cut down. Finely braided rope burns around delicate necks became high fashion. Photographers began keeping records of the soul using glass negatives. To be crowned unthinkable became the rage.

For others the century was a curse. There was the unthinkable factory job, the unthinkable war that led to the next unthinkable war, and the unthinkably cold tenements in the cities. The unthinkable kept looming larger, leading to the unthinkable bomb. And then there’s the unthinkable God enslaved to eternity, and Heidegger’s own unthinkable being thinking in a darkening world.

LOST CREW

Book 6

. . . the victim and the executioner.

–Baudelaire

The snow begins to melt, and the yellowed grass spikes up from a poorly seeded lawn left half-finished by a construction crew. He sits in a parked car thinking it looks more like clumps of hair left after chemotherapy or radiation, or whatever it is we choose to do to ourselves after we discover that it’s too late, that it’s been done to us.

This isn’t to blame the victim, we all are victims, and not to diminish the executioners either. They hone blades on their own histories, which is also us. From that first eye-opening moment when our luminous gray irises float on small fat faces, when we see through it all and never see a thing again, when we are nothings with limitations, it’s really the world falling in on us.

The random patterns turn our small hairless heads, if we have the strength, and no matter which way we look there is something falling into our nothingness. If we cry, the liquid lenses just magnify and bring whatever it is closer and upside down in the sliding of our salts. We can’t stop the faces from falling down on us: mother, father, siblings, all the strangers that we later search for, flipping through photo albums, phone books, skimming rush hour crowds on city streets, for the rest of our and their lives, believing there’s a chance we can resolve, perhaps understand that one haunting glimpse from so long ago.

In jaundiced lighting of airport terminals, slouching in stiff chairs, we exhaust ourselves half-recognizing each traveler who passes, the concourse filling with half-recollections, thinking this is how they might look twenty, thirty years later, leading a child or carrying a briefcase, walking arm-in-arm with someone we should know, smiling, waving goodbye, hello. We must restrain ourselves from running up to them, saying, “Aren’t you . . . ? Did you know . . . ? Do you live in . . . ? Did you go to school at. . . ?” Restrain ourselves if only to save our reputations and conceal the desperation, knowing we carry this same burden around with us, that we are only half recognizable to anyone else, half of what someone’s searching for, yet we will wear out our knees trying to make up the difference with the half of us that hasn’t drifted beyond our reach, the half that someone else is sure they know, though we have never met them before.

He sits in a parked car staring at the snow’s conflagration, the glare off the remaining sooty patches, and flips through the pages of Homer that he has promised himself to read. He catches a movement out the corner of his eye, and wonders if it’s someone who thinks he knows him. Quickly he turns his head, glances in the rearview mirror, but there’s only the smoldering shadow of Troy.

Reviews:

CHEW ON THIS AND IT’S NOT A STICK OF TRIDENT:

A REVIEW OF WALTER BARGEN’S THE FEAST

If one is craving food for thought, The Feast is the book on which to indulge, and the poems within exhibit the type of self-indulgence that poetry should: exploring the link between personal imagination and the means through which it translates into the linguistic: how thought becomes word. These prose-poems sequences display the energy of axons firing signals from receptor to receptor, and the quick-paced language that results could only manifest when there is no insistence on line. The form decodes these impulses into articulate strings of words that resonate in the pit of one’s stomach. Readers find themselves in a state of déja vu when immersed in these poems because, although the content is the product of one man’s imaginative experience, the language springs from an innate common medium: the language of thought itself (mentalese).

Bargen seems to pull this off by bombarding the reader with a seeming overload of sensory input. But this is precisely how human beings take in information and how the mind/imagination turns it over with itself. Thoughts shift more rapidly than a cosmic clock. “Exhausted Spectrum” is a good example of this. (Even the poem’s title indicates its intent.) The poem moves in and out of its character’s (Jonah’s) consciousness. Jonah ponders his existence, his humanity, his mortality while the poem’s speaker expounds the character’s wounds. The poem travels between the internal and the external: “Down the street there are friends missing . . . and then back to Jonah’s more pressing concerns “The wounds shimmer, the preened feathers of plucked angels.” Not only can readers identify with Jonah’s human experience, but seem to be of him as well because the language mimics thought. Think of Einstein when he first imagined himself riding beams of light. This is not to say that the poems are difficult to follow„Ÿone simply enjoys the word and image play and allows him/herself to be transported to wherever the poems go. When in the presence of nerve impulses firing at lightning-like speed, what else can one do but become immersed in the genius that language is in translating thought.

However, because language is largely an arbitrary system, the translation process produces a loss of purity. It is indeed when humans articulate their perceptions that all went awry; it is, perhaps when we fell from grace because we had a tool with which to question. It isn’t so much that we were innocent from the get go and that language corrupted us: it is that we were able to express whatever dark curves our thoughts sometimes strayed to. Anything that one can imagine is possible, but it is words that make imagination imminent. Bargen expresses this throughout the book but perhaps best in the poem “The Blue and Black Book.” The poem begins:

In a small unnamed Baltic town, close enough to the sea that one can smell the salt crystallizing in the tidal winds sighing inland each day during the summer months, there was to be found„Ÿtaking a deep breath that expands the chest into a false sense of belonging to something eternal„Ÿa true hint of a beginning.

That opening sentence demonstrates the type of seeming digressionary overload of the sensory mentioned earlier, but it also served in communicating what I see as the books main agenda: the thought/language continuum and its effect on the human psyche. The poem, in the second stanza, continues:

On the crowded walls of his small room hung souls frowning with the look of those drowning in deep thoughts. He sat troubled. If in the beginning was the Word„Ÿa clearly spoken, though assuredly and not easily understood one„Ÿthen innocence never existed, since every true word is married to its false compliment. So, if the in the beginning was the Word, then also, in the beginning was not the Word. As soon as something was heard, it was not heard.

If one has ever paid attention to what one is thinking, in any significant way, one will recognize that this is the way thoughts fleet. And perhaps this nature of thought„Ÿthe speed, as well as the conflict between poles is what causes the inherent conflicts within human beings. But it is also what makes us beautiful. When language is true as it is in these poems, we are redeemed.

Jen Reid

REDACTIONS 4/5

p 66-67